Human Rights and Aged Care

By Josh De Voogel[1]

Summary

Will a Human Rights approach improve the Quality of Care in Aged Care?

A human rights-based approach is a conceptual framework based on international human rights standards for ensuring that the rights of individuals are at the centre of policy and practice.

In reconceptualising Australia’s obligations to its older people, seeing them not as vulnerable but as active right holders, this approach has the ability to improve the standard of care delivered by aged care providers.

What benefits will it deliver?

- Targeted and consistent policy developments.

- Reframed legal responsibilities, with an onus on enhancing the accountability of aged care providers to provide high-quality care that is consistent with human rights principles.

- Improvement of services by providing education and training grounded in respecting the autonomy and dignity of care recipients.

- Reshaped broader community attitudes towards Australia’s ageing population.

Remedies for individuals

Currently

The Charter of Aged Care Rights is maintained by the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, which receives and acts on the basis of formal complaints. Whilst comprehensive and transparent, the Charter suffers from a lack of enforceability and no attached penalties for breach.

The domestic human rights framework is enforced by the Australian Human Rights Commission, which takes complaints of unlawful discrimination and attempts conciliation. Matters can also be further pursued to the Federal Court of Australia or the Federal Circuit Court for an enforceable remedy.

Civil law avenues of recourse are available where care has been delivered so inadequately as to amount to negligence, false imprisonment or other tortious actions.

Australia has agreed to be bound by United Nations complaint mechanisms separate from those under domestic legislation. These avenues will likely only be enlivened in extreme circumstances and when all other remedies available in Australia are exhausted.

Proposed

Under Recommendation 14 of the Royal Commissions into Aged Care Quality and Safety, a general, non-delegable, positive statutory duty is proposed that ensures that the care delivered by aged care providers is of high quality and safety, so far as reasonable.

Compliance with the duty is recommended to be maintained with civil penalties enforced by the Quality Regulator, where failure to provide high-quality care exposes a resident to a risk of harm.

Introduction

Aged care advocates often advocate for the increased reliance upon human rights standards in aged care.

Reference is often made to person-centric care, rights to safe and high-quality care, and to be treated with dignity and respect, including with respect to diversity and culture.

This article looks at defining human rights in aged care settings and how and to what extent respecting such rights can make a difference in improving the welfare of recipients of care.

1. Human Rights Relevant to Aged Care Settings?

Human rights are about improving the quality of life.

Human rights are basic rights and freedoms applicable to every person, as set out in international treaties and conventions.[2] Their existence promotes and protects the intrinsic value of human life, the identity of the individual, and their entitlement to an adequate standard of living.[3]

The provision of adequate care and protection for the older population raises critical human rights issues in Australia. The aged care sector is responsible for providing a range of services to support older Australians in their daily lives, including healthcare, social support, and accommodation. However, there have been increasing concerns about the quality of care and the adequacy of human rights protections for older Australians in aged care settings.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (‘The Royal Commission’) has brought to the forefront the significant challenges faced by older Australians in accessing quality care and the need for fundamental reform in the aged care sector.[4] The Royal Commission has identified significant human rights concerns in aged care, including neglect, abuse, and mistreatment of older Australians.[5]

This paper refers to international and domestic sources of law that pertain to human rights particularly relevant for Australian aged care residents, discusses the key recommendations of the Royal Commission, and examines the ability of these proposals to protect the human rights of older Australians.

2. Sources of Human Rights in Aged Care Settings

There are numerous domestic laws relating to, and international sources of, human rights, with varying levels of ratification and influence in Australia. Domestic and international sources of law that have been identified as having some applicability to aged care settings in Australia include the following:

International Law ratified in Australia

There are a number of international treaties and conventions that Australia has ratified which contain provisions relevant to the human rights of older people.

Such ratified treaties, themselves, provide guidance only to domestic lawmakers. Their provisions are not legally enforceable save when implemented by domestic legislation. These treaties include:

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[6]

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) [7]

- Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)[8]

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)[9]

- International Covenant on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD)[10]

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)[11]

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)[12]

Broadly speaking, the above human rights instruments above require that Australia respect the relevant human rights by not interfering in the enjoyment of those rights, protect the relevant human rights from third parties, and fully realise the rights by adopting appropriate measures.[13] A summary of the rights included in the above instruments is contained below:[14]

| ICCPR | |

| Art 9 | The right to liberty and security |

| Art 12 | The right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose one’s residence |

| Art 7 | The right to freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment |

| Art 17 | The right to freedom from arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy, family and home |

| Art 18 | The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, including the freedom to manifest one’s religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching |

| Art 26 | The right to equality before the law without discrimination |

| Art 27 | The right for persons from ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities to enjoy their own culture, profess and practice their own religion, or use their own language |

| ICESCR | |

| Art 12 | The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health |

| CRPD | |

| Art 16 | The right of persons with disabilities to be protected from all forms of exploitation, violence and abuse |

| Art 19 | The right of persons with disabilities to live independently and be included in the community |

| CEDAW | |

| Art 12, Art 13 | The right to freedom from discrimination on the basis of sex, including in relation to the provision of goods, services and facilities |

| ICERD | |

| Art 5 | The right to freedom from discrimination on the grounds of race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin, including in the provision of goods, services and facilities |

| UNDRIP | |

| Art 24 | The right of Indigenous peoples to maintain their health practices and have access, without any discrimination, to all social and health service |

| Art 24 | The right of Indigenous peoples to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health |

As to enforcement, Australia has agreed to be bound by the United Nations complaint mechanisms associated with several ratified treaties, such as the ICCPR, ICERD, CEDAW, CRPD and CAT, which have complaint mechanisms separate from those offered under domestic legislation.[15] Actions under these procedures would be against Australia as a UN Member State and signatory to the above treaties and their protocols, causes of action would likely only be enlivened when all other remedies (if any)available in Australia are exhausted.[16]

Other International Sources of Law

Aside from these ratified instruments, there are also several non-binding “soft law” sources of international law which pertain to older people. First, the 1982 World Assembly on Ageing adopted the Vienna International Plan of Action on Ageing (VIPAA). This includes recommendations to avoid the segregation of older people and to make available home-based care for older persons available.[17]

This was followed by the 1992 Madrid International Plan of Action (MIPAA), an updated version of VIPAA.[18] The three main goals established were:

- the full realisation of fundamental rights and freedoms for older persons;

- ensuring the full enjoyment of the economic, social and cultural rights and the civil and political rights of older persons, and;

- the elimination of all forms of violence and discrimination against older persons. MIPAA has since guided domestic and international dialogue concerning older people.

The 1991 United Nations Principles for Older People is a guiding, non-binding international instrument which contains 18 principle which encourages governments to incorporate them into their programs.[19] The principles relate to independence, participation, care, self-fulfilment and dignity. Examples of principles include:

- Older persons should be able to live in environments that are safe and adaptable to personal preferences and changing capabilities;

- Older persons should be able to reside at home for as long as possible;

- Older persons should be able to utilise appropriate levels of institutional care, providing protection, rehabilitation, and social and mental stimulation in a humane and secure environment;

- Older persons should be able to enjoy human rights and fundamental freedoms when residing in any shelter, care or treatment facility, including full respect for their dignity, beliefs, needs and privacy and for the right to make decisions about their care and the quality of their lives.

A more recent development has been the establishment of the UN Open-Ended Working Group on Ageing (OEWG).[20] Since 2020, the OEWG has brought together annually Member States, National Human Rights Institutions, NGOs and UN agencies to discuss ways to strengthen the protection of human rights for older persons. The discussions aim to identify inequalities in law and in practice and explain what changes need to be made for the human rights of citizens to be foregrounded and protected in their older age.[21]

Australian Law

Under Australian law, ratification of international treaties and agreements has led to a nationalised framework of legislation that serves to broadly protect human rights. The principal laws are:

- The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) which deals with discrimination on the grounds of race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin and racial hatred.[22]

- The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) which deals with discrimination on the grounds of pregnancy, marital or relationship status (including same-sex de facto couples) status, breastfeeding, family responsibilities, gender identity, intersex status, sexual orientation and sexual harassment.[23]

- The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) which deals with discrimination on the grounds of disability.[24]

- The Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth) which deals with discrimination on the grounds of age.[25]

- The Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) which provides limited rights in relation to specific international instruments such as the ICCPR and the CRPD.[26]

The above human rights framework is “enforced” (to a degree) by the Australian Human Rights Commission. It receives complaints of unlawful discrimination and attempts conciliation. Unresolved complaints can also be further pursued to the Federal Court of Australia or the Federal Circuit Court for enforceable remedies.

PANEL Principles

The PANEL Principles are a set of guiding principles developed by the Australian Human Rights Commission to ensure that the human rights of older Australians are upheld in aged care settings.[27] The PANEL Principles include:

- Participation and engagement;

- Access to information and education;

- Non-discrimination and social inclusion;

- Empowerment and choice;

- Life and dignity.

The PANEL Principles provide a useful framework for improving the welfare of aged care residents. By promoting participation, access to information, and empowerment, the PANEL Principles aim to ensure that aged care residents are active participants in their care and have the opportunity to make informed decisions about their lives. In particular, principles of non-discrimination and social inclusion aim to prevent ageism and ensure that aged care residents are treated with dignity and respect.

Charter of Aged Care Rights

Relevant to consumers of Aged Care is The Charter of Aged Care Rights.[28] The charter adds to existing rights under Australian law and offers aged care consumers a broad swathe of rights whilst receiving aged care services. Under the Charter, consumers have a right to:

- safe and high-quality care and services;

- be treated with dignity and respect;

- have their identity, culture and diversity valued and supported;

- live without abuse and neglect;

- be informed about their care and services in a way they understand;

- access all information about themselves, including information about their rights, care and services;

- have control over and make choices about their care and personal and social life, including where the choices involve personal risk;

- have control over, and make decisions about, the personal aspects of their daily life, financial affairs and possessions;

- their independence;

- be listened to and understood;

- have a person of their choice, including an aged care advocate, support them or speak on their behalf;

- complain free from reprisal, and to have their complaints dealt with fairly and promptly;

- personal privacy and to have their personal information protected;

- exercise their rights without it adversely affecting the way they are treated.

Everybody involved in the delivery of care to an aged person must respect their rights.

Aged care providers must assist residents and their families in understanding their rights. Oversight of these rights is maintained by the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, which receives and acts on the basis of formal complaints. Whilst comprehensive and transparent, the Charter suffers from a lack of enforceability with no attached penalties for breach. The Royal Commission has therefore recommended a new Aged Care Act with a different formulation of rights for Australian aged care residents and improved enforceability measures.[29]

3. How will a new Aged Care Act include Human Rights?

The human rights of older Australians applicable in aged care settings received significant coverage in the Royal Commission, with several of its 148 recommendations pertaining to how a new Aged Care Act and how it should serve to protect human rights for aged care residents.[30]

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety

Recommendation 2 of the Royal Commission is focused on the rights of older people receiving aged care.[31] It states that a new aged care Act should:

- Specify a list of rights applying to people seeking and receiving aged care;

- Declare that the purposes of the new Act include the purpose of securing those rights and that the rights may be taken into account in interpreting the Act and any instrument made under the Act.

The recommendation’s list of rights includes:

- for people seeking aged care:

- the right to equitable access to care services

- the right to exercise choice between available services

- for people receiving aged care

- the right to freedom from degrading or inhumane treatment or any form of abuse

- the right to liberty, freedom of movement, and freedom from restraint

- the right of autonomy, the right to the presumption of legal capacity, and in particular, the right to make decisions about their care and the quality of their lives and the right to social participation

- the right to fair, equitable and non-discriminatory treatment in receiving care

- the right to voice opinions and make complaints

- for people receiving end-of-life care, the right to fair, equitable and non-discriminatory access to palliative and end-of-life care

- for people providing informal care, the right to reasonable access to support in accordance with needs, and to enable reasonable enjoyment of the right to social participation

The executive summary of the Royal Commission’s Final Report revealed the basis for their recommendation and list of rights. It recognised a strong community desire for two key fundamental rights: dignity and respect.[32] The overwhelming sentiment throughout the Commission’s hearings was for the dignity of all aged care recipients to be upheld and that their value as an individual and members of society be respected.[33]

Stemming from these two core values are the aged care-specific rights of control and choice, relationship with and connections to communities, good quality of life, and ability to age at home. Control and choice are about giving residents self-determination and personal autonomy, allowing them to be actively involved in their decision-making. Relationships and connections embrace fostering strong relationships which make aged care recipients feel heard and seen and keep them engaged, valued and socially connected. Finally, quality of life should be a constant and predominant aim of the aged care system. Ageing at home must also be recognised as central to a person’s sense of identity and independence.[34]

The Royal Commission also recognised Australia’s obligations under international human rights instruments and made special note of Art 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”.[35]

4. Enforceability

The Commission stated that, with the exception of the freedom from restraint, the proposed rights in Recommendation 2 should not be separately and directly enforceable in the courts. It advocates instead for viewing these rights as aspects of a general duty imposed on aged care service providers to deliver high-quality care.[36]

This general duty is found under Recommendation 14;

- A general, positive and non-delegable statutory duty on any approved provider to ensure that the personal care or nursing care they provide is of high quality and safe so far as reasonable, having regard to:

- The wishes of any person for whom the provider provides or is engaged to provide that care,

- Any reasonably foreseeable risks to any person to whom the provider provides or is engaged to provide that care; and

- Any other relevant circumstances.

The meaning of ‘High-quality care’ under this general duty is clarified in Recommendation 13:[37]

- High-quality care puts older people first. It means a standard of care designed to meet the particular needs and aspirations of the people receiving aged care. High-quality care shall:

- Be delivered with compassion and respect for the individuality and dignity of the person receiving care;

- Be personal and designed to respond to the person’s expressed personal needs, aspirations, and their preferences regarding the manner by which their care is delivered;

- Be provided on the basis of a clinical assessment and regular clinical review of the person’s health and well-being, and the clinical assessment will specify care designed to meet the individual needs of the person receiving care, such as the risk of falls, pressure injuries, nutrition, mental health, cognitive impairment and end-of-life care;

- Enhance to the highest degree reasonably possible the physical and cognitive capacities and the mental health of the person;

- Support the person to participate in recreational and social activities.

In drafting Recommendation 13 and the definition of high-quality care, it is clear the Commission had regard to the fundamental human rights it was trying to protect, explicitly referencing ‘respect’, ‘dignity’, ‘individuality’, ‘personal preferences’ and ‘social … engagement’. This formulation of high-quality care was also informed by community sentiment and industry understanding, with a number of studies revealing ‘salient characteristics’ that aligned with a human rights approach.[38]

To ensure compliance with this general duty, the Commission recommends that any failure to comply with the duty where that failure exposes a resident to a risk of harm will expose a provider, and its key personnel, to a civil penalty by the Quality Regulator. The provider may also be required to compensate a resident harmed by the failure.[39]

Whilst this is an important step in establishing consequences for providers in failing to provide high-quality care, the language does not make it clear if there are consequences for providers who fail to comply with the general duty but do not expose the resident to a risk of harm. However, before a new Aged Care Act is enshrined in law, these recommendations are nothing more than that: recommendations of changes that need to be made to address the issues uncovered by the Royal Commission.

5. If enacted, will a new Aged Care Act that includes the Royal Commission’s recommendations protect the human rights of Australian aged care residents?

The new Aged Care Act, proposed by the Royal Commission, would provide a more comprehensive and consistent framework for protecting the human rights of aged care residents in Australia. By enshrining the rights of aged care residents in law, the new Act it envisaged would provide a clear and enforceable standard for aged care providers to follow, one that goes beyond the existing Charter of Aged Care Rights and PANEL principles, referred to above.

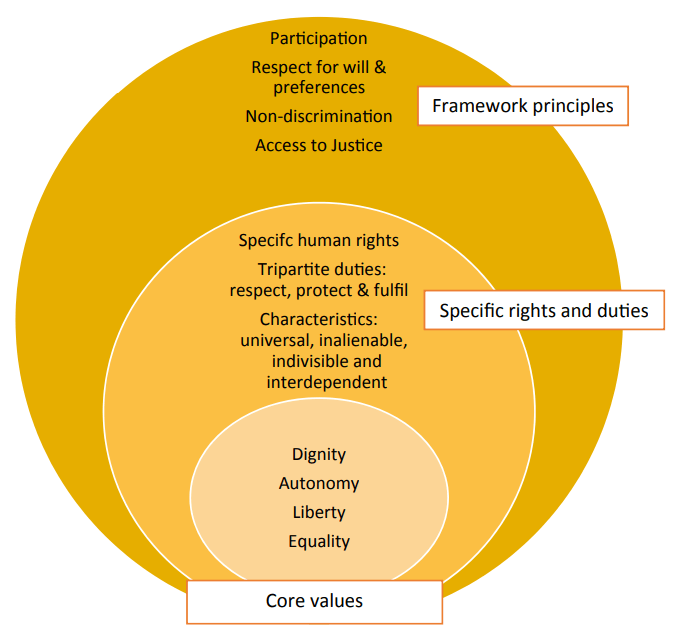

The proposed new Aged Care Act would also, importantly, be grounded in a human rights-based approach.[40] Such an approach is a ‘conceptual framework based on international human rights standards for ensuring that the rights of individuals are at the centre of policy and practice.[41] This approach serves to foreground human rights as the core values which inform all other processes and behaviours. It has been touted as effective in the United Kingdom, with a human rights-based approach applied to the aged care sector through its Human Rights Act (1998).[42]

This human rights-based approach is important in offering the potential to reconceptualise our responsibilities towards older Australians, seeing them as not vulnerable second-class citizens in need of protection but active rights holders.[43] Such an approach has the potential to not only improve the standard of care in aged care facilities but also to reshape community attitudes towards Australia’s ageing population and reframe legal responsibilities, policies and procedures.[44]

Figure 1: A Human Rights-Based Framework

However, the effectiveness of the Commission’s proposed new Aged Care Act and its human rights-based approach will depend on a number of factors. First, the Act will need to be properly resourced and implemented with adequate funding and support for aged care providers to comply with its provisions. These issues of funding and support were aptly identified in the Royal Commission’s Report. The proposed new Aged Care Act is only part of a broader suite of reforms that will be needed to improve the quality and safety of aged care residents in Australia.[45] Other recommendations from the Royal Commission, such as increasing funding for aged care,[46] improving workforce training and development,[47] and addressing the root causes of systemic issues in the sector, will also all need to be implemented to ensure the human rights of aged care residents are fully protected.[48]

In addition, there are some potential challenges to the effectiveness of the proposed new Aged Care Act. For example, the jargonistic language of human rights legislation may make it difficult for aged care residents and their families to understand their rights and how to enforce them. The Act will need to be communicated in a clear and accessible way to ensure that it is widely understood and applied, especially by aged care recipients and their families.

Further, effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms will be needed to ensure that the human rights of aged care residents are being upheld in practice. The current system provides little recourse for aggrieved aged care residents, with internal complaint procedures often ineffective and the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commissions complaint process involving long delays and being burdensome on residents. The enforceability of a general duty of high-quality care (discussed above) is promising, even if curtailed by the requirement of a risk of harm. However, a system that moves the onus away from vulnerable aged care residents and their families reporting incidents and employs a more rigorous approach of oversight, with ongoing investment in regulation through regular audits and inspections of facilities, is preferred.

Get Help

If you or someone you know needs legal assistance, we encourage you to fill out Aged Care Justice’s GetHelp form on our website at www.agedcarejustice.org.au; or contact Aged Care Justice on (03) 9016 3248; or email us on info@agedcarejustice.org.au. You may then select, or, if you wish, we will direct you to, one of our Allied Law Firms for an initial meeting and advice, at no cost to you. Thereafter, you can decide whether to proceed with a formal legal complaint. If you do wish to proceed, costs arrangements, if any, will need to be discussed, and agreed, with the firm.

Sources:

[1] Law student and ACJ volunteer.

[2] Australian Human Rights Commission, ‘Fact Sheet 1: Defining Human Rights’, Human Rights Explained (Website) <https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/education/human-rights-explained-fact-sheet-1-defining-human-rights>.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (Final Report Volume 1, March 2021) (‘R.C. Final Report’)

[5] Ibid.

[6] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1996, 993 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976).

[7] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 993 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 January 1976).

[8] Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 10 December 1984, 1465 UNTS 85 (entered into force 26 June 1987).

[9] Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, opened for signature, 18 December 1979, 1249 UNTS 13 (entered into force 3 September 1981).

[10] International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, opened for signature 21 December 1965, 660 UNTS 195 (entered into force 4 January 1969).

[11] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, opened for Signature 30 March 2007, 2515 UNTS 3 (Entered into Force 3 May 2008).

[12] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, GA Res 61/295, UN GAOR, 61st Sess, 107th Plen Mtg, Agenda Item 68, Supp No 49, UN Doc A/RES/61/295, Annex, (2 October 2007) 295.

[13] Australian Human Rights Commission, A Human Rights Perspective on Aged Care (Report, 18 July 2019) 10 [45].

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid 12-13 [51].

[16] Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, ‘Complaints about human rights violations’, (Website) <https://www.ohchr.org/en/treaty-bodies/complaints-about-human-rights-violations>.

[17] United Nations, Report of the World Assembly on Aging, A/CONF.113/31 (1982) 84.

[18] Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing, A/CONF.197/3 (8-12 April 2002).

[19] United Nations Principles for Older Persons, GA Res 46/91 (16 December 1991).

[20] ‘UN Open-Ended Working Group on Ageing – OEWG’, AGE Platform Europe, (Website) <https://www.age-platform.eu/un-open-ended-working-group-ageing-oewg>.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).

[23] Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth).

[24] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth).

[25] Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth).

[26] Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth).

[27]Australian Human Rights Commission (n 12) 14 [57].

[28] Aged Care Act 1997 (Cth) s 96(1), Schedule 1 User Rights Principles 2014.

[29] Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, Charter of Aged Care Rights (Booklet).

[30] See generally R.C. Final Report (n 3).

[31] Ibid 206.

[32] Ibid 78-79

[33] Ibid 78-79.

[34] Ibid 78-79.

[35] Ibid 79-80.

[36] Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (Final Report Volume 3A – A New System, March 2021) 97-99.

[37] Ibid 92-94.

[38] Ibid 89.

[39] R.C. Final Report (n 3) 91.

[40] Ibid 79-80.

[41] Bridget Lewis, Kelly Purser and Kirsty Mackie, The Human Rights of Older Persons (Springer Singapore, 2020) 67.

[42] Human Rights Act 1998 (UK); Australian Human Rights Commission (n 12), 16 [59].

[43] Lewis, Purser and Mackie (n 40) 68.

[44] Ibid.

[45] See generally R.C. Final Report (n 3).

[46] Ibid 149-156.

[47] Ibid 124-128.

[48] Ibid.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this article are the views of the author. The contents of this article are for general information purposes only and do not constitute legal advice, are not intended to be a substitute for legal advice, and should not be relied upon as such. Legal advice should be sought prior to any action being taken in reliance on any of the information. If you need legal support, please contact Aged Care Justice, who can provide access to legal assistance.